Call for papers: Papers are invited for a special issue entitled “New Work on Electronic Literature and Cyberculture.” Ed. Maya Zalbidea Paniagua (Universidad La Salle Madrid), Mark Marino (University of Southern California), and Asunción López Varela-Azcárate (Universidad Complutense Madrid). CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.5 (2014):http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/

Author: Sarah Lozier

As a humanities graduate student interested in looking at digital media, digital processes, and digital sociality, it is tempting to define myself professionally as a Digital Humanities scholar. But this definition isn’t particularly helpful, since it almost always elicits the response — “And what does that actually mean?” Indeed, being a DH professional seems to “mean” differently for different people, and these definitional slippages become increasingly problematic when it comes to those non-research necessities of being an aspiring academic (getting jobs, applying for grants, and teaching undergraduates). In an effort to think through some of these slippages and their politics, I’d like to look at one specific resource for DH professionalization — the University of Victoria’s Digital Humanities Summer Institute (DHSI) — to think about what this program suggests effective DH professionalization is and does.

The DHSI is “a week of intensive coursework, seminars, and lectures,” all focused around issues pertinent to the digital humanities. This year’s twenty-seven seminars cover a wide range of topics ranging from “Text Encoding Fundamentals” to “Electronic Literature in the Digital humanities,” but all twenty-seven are organized along a kind of divide between building digital skill sets — coding, software use, etc — and dealing with fairly traditional issues of humanities study applied to digital objects — “reading” electronic literature, applying “theory” to digital media, etc.

This divide strikes me as potentially indicative of the larger problem of professionalizing in DH, and that is the question of what a DH professional does. While these seminars cover topics dealing explicitly with navigating the Digital and topics dealing explicitly with navigating the Humanities, there aren’t any seminars that explicitly deal with digital AND humanities navigation, DH as one unit. They suggest that DH is still D and H, Digital and Humanities. The problem with this “and” is analogous to the problem of the hyphen conceived as the splice that Katherine Hayles discusses in the fifth chapter of How We Became Posthuman. That is, D (and) H imagines a “separate but equal” relationship between the items on either side of the and, even as it officially splices them together (DH) as one item. Scholars who do this thing called “DH” must actually do “D and H,” making the discipline a necessarily exclusive rather than inclusive one. In the hectic world of the modern academy, where tenure is disappearing and we are asked more often than not to work “for free,” today, being a DH professional is all but closed off to those who already have the time and resources to equivalently pursue D and H — established, funded academics. Until we can more effectively splice D and H into DH, this exclusivity and definitional slipperiness will continue to exist.

UCR’s Critical Digital Humanities and Medical Narratives Mellon research groups are hosting a Lunchtime Lightning Talks Event, Transgressive Research Methods: What Happens when the Humanities Engages with Science? on October 24, 2013 from 11:30 – 1:00 in HMNSS 2212. This event is open to faculty, graduates, and undergraduates, and lunch will be provided.

This Discussion-Based event will take the form of 5-7 minute “Lightning” talks, presented by faculty and graduate students. These quick interventions will focus on the ethics, values, limitations, and possibilities of interdisciplinary research methods, with the goal of generating inquiry, reflection, and discussion among the participants around the following, and other related, issues:

What features characterize “truly interdisciplinary” research?

How does the blend of methodologies, topics, and questions from across humanistic and scientific disciplines both limit and/or expand our notions of Research?

What are the ethical considerations involved in cross-disciplinarity?

How do we assign (or reject) value to work that straddles disciplinary borders?

How does the future of the disciplined academy and academic work appear, as grants and honors become more available to work that claims “interdisciplinarity.”?

We look forward to your participation at what promises to be a lively, critical, and thought-provoking event! If you have any questions, please contact Sarah Lozier at slozi001@ucr.edu or Kyle Harp at kharp001@ucr.edu.

Sincerely,

The Critical Digital Humanities and Medical Narratives Mellon Workgroups

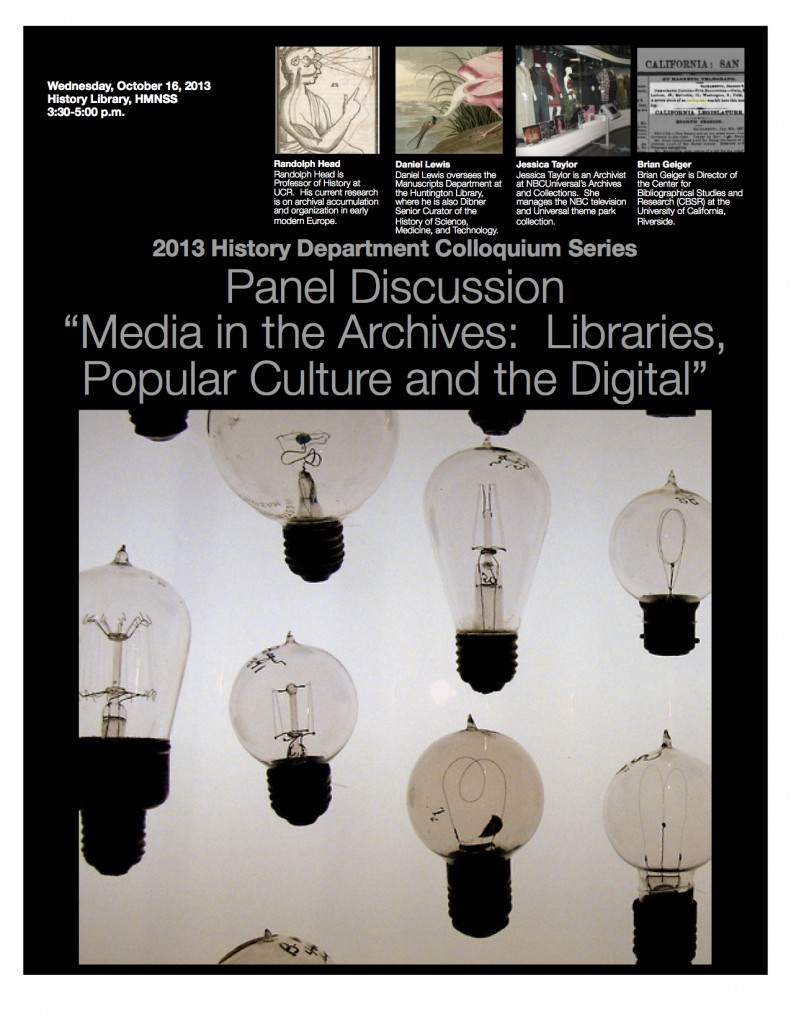

Review: “Media in the Archives: Libraries, Popular Culture, and the Digital” Panel Discussion

October 18th, 2013

Kimberly Hall

by Sarah Lozier

On October 17th, 2013 I had the opportunity to attend a panel discussion hosted by UCR’s History Department on the topic of Media in the Archives. In general, the panelists described various forms that archival work can take, whether one is working in an academically-supported research archives like the Huntington, a corporate pop-cultural exhibition-supported archived like that of NBCUniversal, or a digitized archive of material documents like the California Digital Newspaper Collection (CDNC). Given the range of archives presented, it is no surprise that there were many different strategies for navigating the challenges and perks of archival work. What was perhaps, more surprising, was that there were nearly as many similarities as differences presented, particularly among theoretical axes of authenticity and originality. Here, however, I’d like to focus on one archival issue in particular that did not get much attention, but that can be particularly provocative when material and digital cultures and archives collide—the issue of the User.

The User did enter the conversation yesterday when Brian Geiger described the invaluable role of the untrained, amateur user to correct errors in the text that occur in the digitization process due to the limits of computer-based text recognition. Dr. Geiger pointed out that allowing these amateur users this level of access to affect and change the archival material is a bittersweet affair. On the one hand, it frees up the trained, degree-holding archivists to spend time on work that requires the specialist’s hand; while at the same time potentially expediting the digitization process, and with fewer mistakes, due to an increased human labor force. (This introduces the problem never far from DH labor discussions of Crowd-Sourcing, but that is best saved for another post). On the other hand, the CNDC is still an institutionally accredited archive, and there are very real possibilities that this untrained labor force is introducing as many (if not more damaging) errors to the archival materials than the computer. Indeed, the untrained user could only get this kind of access to a digital archive; the very notion would be unthinkable for a material and physical archive like the Huntington or NBCUniversal’s Archives, where the “user” is either a trained researcher operating under the watchful eye of the archivist, or a spectator who is encouraged to Look-Don’t-Touch.

So who is the archive’s User? What does it mean to really use an archive? Can using be limited to accessing? Or can it be expanded to include interacting, as in the shift of replacing “reader” with “user” in conversations about e-Lit? What are the stakes and potential effects of this conceptual expansion, particularly given the slippery place of labor in accessing, using, and interacting? Are we, the institutionally-supported and access-granted DH scholars, the Privileged Users, willing to support this?

by Ian Ross

The pedagogical implementations of digital technology have been widely hailed, but are frequently implemented in the form of making traditional pedagogical procedures more conveniently accessible (online classrooms, digital office hours, etc.). However, there is a largely ignored degree to which digital production by students is helpful to composition, comprehension, and critical thinking in the classroom. Unfortunately, the primary roadblock to pedagogical digital production in curriculum centering around this production is the inaccessibility of coding as a means of that writing. However, if this process can be made more accessible, the constructed nature of binary code, as well as its inability to work with logical fallacy, has the potential to illustrate much clearer narratological and argumentative skills to novice writers.

In an attempt to work around this problem, I have enacted a classroom project based around the free and universally available program Inform7, an interactive text based video game production space designed to use English language “coding” to create digital spaces with which the audience can interact. The first attempt at this project involved individual students building games using a peer produced message board for guidance, produced limited results, and ended with most students circulating around an “expert” with previous experience. However, the second attempt was designed as a group project and guided by a greater amount of classroom instruction. Students in groups of four posted their games along with the code, and were asked to play the games designed by the three other groups before looking at the code that Inform7 translated into gameplay.

This structure created an identifiable divide between author and audience, and allowed for a direct discussion of narrative production, symbol, icon, and metaphor. The program uses binary logic (i.e. one thing cannot be two things) within an English language code to produce games. Giving “objects” (which are defined by description, portability, and/or their ability to contain other objects) names helped students understand the arbitrary nature of language and concepts like simulacra. For instance, a container is given size by the decoding audience: there is no difference between a “wallet” and a “bucket” unless the programmer provides a difference. Using language to define meaning, and illustrating the degree to which this takes place in everyday life is a central benefit to this project.

Putting the student in the position of the creator allows the student to more clearly understand how creation takes place as well. In my second attempt with this project, students worked around coding limitations in ways that were not apparent to their intended audience when playing. One group built a door called “the laptop”, locked it with “the flashdrive” and then named each attached room a different URL address. This created a user experience of interacting with a spatially static computer, while the translating program understood what was happening as geographical movement and location. Once students outside of the group both looked at the code designed to create this world and had played the game itself, they began to comprehend the degree to which

narrative can potentially step outside of perceived media limitations. Additionally, students who either built or played this specific game were then able to more clearly engage in close reading and authorship when they were confronted with the digital illusion of reality, as well as understand the benefits and meaning production of metaphor.

These were only a few of the ways integrating this process into classroom activity allowed for a deeper and more apparent discussion of the abilities one has access to as a writer as well as the methods of readership which take place invisibly around various socially constructed symbols. Allowing for programs like Inform7, and for the creation of more specialized programming in the classroom like it, is the first important step to bridging the digital divide in a way that will provide students with clear pedagogical connections to necessary comprehension and critical thinking skills.

For those curious, the links to Inform7 (the program used to build these games) and Frotz (the program used to play them) are below. Think of Inform7 as the software (i.e. videogame disc) and Frotz as the hardware (Console system) if the process seems confusing:

Media in the Archives: Libraries, Popular Culture, and the Digital

October 12th, 2013

Steve Anderson

Please join the panel discussion this Wednesday, October 16, 3:30-5pm (History Library) on “Media in the Archives: Libraries, Popular Culture, and the Digital,” moderated by UCR History Professor Randy Head and featuring Dr. Dan Lewis (head of manuscripts and Dibner Senior Curator of Science, Medicine, and Technology), Jessica Taylor (NBC Universal Archives and Collections), and Dr. Brian Geiger (UCR Center for Bibliographical Studies and Research). Note that all of these organizations have a track record of hiring UCR grad students and have paid internships.

Response by Rochelle Gold

Every September, the new MLA Job Information List (JIL) offers a snapshot of the state of the field for literary scholars. Roopika Risam’s recent blog post “Where Have All the DH Jobs Gone?” points out that in spite of the hype around digital humanities as the next big thing, digital humanities job opportunities are dwindling. After reading through the JIL, Risam concludes that while a number of job postings, including 17 literature positions, call for digital humanities as a secondary area of expertise, very few postings seem to look for digital humanities as a primary research field. As a result, she argues that “the explicitly DH job is perhaps the most endangered species on the JIL.” To her credit, Risam specifies throughout her blog post that her results are necessarily tentative as job postings are continuously added to the MLA job list throughout the fall. Nonetheless, it is hard to fully understand to what extent Risam’s point about the digital humanities becoming “endangered” makes sense without more context of the humanities job market as a whole. We especially need to know how the number of digital humanities jobs compares to other subfields. I accessed the job list several weeks after Risam to see if her conclusions hold. As Risam herself points out, the JIL can be unwieldy as different search terms yield different results. I will give just a few partial yet suggestive examples. The search terms “Victorian” and “19th century” yielded nine and 11 results respectively. On the other hand, “digital media” and “digital humanities” generated 27 and 32 results. My unscientific tinkering on the JIL points to the extremely harsh realities of the job market overall. While the digital humanities job pool may be shrinking, this seems to reflect the broader trend of the disappearance of jobs in literature and the humanities. Comparatively, digital humanists are probably still faring a little better than the rest, but, of course, that is not saying much at all.

Read Risam’s original post here: http://roopikarisam.com/2013/09/15/where-have-all-the-dh-jobs-gone/

The Politics of DH Professionalization

While the digital sphere has often been understood as a disembodied site of engagement, scholars within DH are increasingly challenging the field to examine its own universalizing tendencies that privilege the white, male producer. As Moya Bailey suggests[i], the increasing visibility of the field calls for an increasing reflexiveness about its own politics: “The move ‘from margin to center’ offers the opportunity to engage new sets of theoretical questions that expose implicit assumptions about what and who counts in digital humanities as well as exposes structural limitations that are the inevitable result of an unexamined identity politics of whiteness, masculinity, and ablebodiness.” The question of “what and who counts” as DH scholarship includes an inherent ability bias, as well as a reclamation of masculinities often labeled “geek” or “nerd.”

As a self-proclaimed “big-tent” field, DH proposes an engaging model of scholarship that embraces interdisciplinary, collaborative approaches that challenge the field and period-specific approaches of many traditional humanities departments. But are those claims valid if the field isn’t aware of its own politics of privileging certain types of users and scholarship? Can we read certain texts, such as the DH Manifesto, as endorsing certain modes of engagement while excluding others? What are the challenges to making the field more engaged with its own biases? What are the possibilities of addressing these politics before the borders of the field become solidified?

The stakes of such questions become apparent with even a quick reading of the last two MLA JIL. While Roopika Risam laments the drop in DH jobs this year, the wide array of posts seeking DH skills as either a primary or secondary specialty suggest the continued appeal of the field. Given the discussion of the possible politics of the field, what does it mean to market yourself as a DH scholar? Even more importantly, what is at stake for young scholars, particularly job seekers, to offer alternative forms of DH scholarship? What would those forms look like and what do they offer that is currently missing? Are there institutional politics that determine the types of DH scholarship or skills privileged? Are there already important reparative politics within DH that need to be recognized? Does the skill bias within the field limit the types of scholars and scholarship possible within DH? Is it possible to be both a DH scholar and a cultural/historical/literary critic and what are the sites of enrichment and tension between these practices? How do you understand your own position within the field as a young scholar and how do these questions emerge in your own research? Are these important questions to consider or is there another, similarly important agenda that DH is advancing?

[i] Bailey, Moya Z. “All the Digital Humanists are White, All the Nerds Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave.” Journal of Digital Humanities 1: 1 (Winter 2011) n.p. Web.

CFP: “New Media and Surveillance” Teaching Media Quarterly 2(1): 2013

September 30th, 2013

April Durham

Call for Proposals:

In recent years, there has been a continued proliferation of social media platforms (like Facebook and Twitter), recording and video-streaming devices (like TiVo and Apple TV), and online “deal-of-the-day” services (like Groupon and Living Social). As individuals participate in these platforms and services, we open ourselves up to new forms of surveillance and monitoring, not only by state authorities but also by private marketers. A whole new industry of social media analysis has been created that aims to perfect algorithms in order to turn personal user data into profit. While some may welcome “customized advertising,” the data mining processes that have emerged over the past few years have far-reaching implications for our everyday lives. Teaching Media Quarterly is seeking materials that critically explore the relationship between surveillance and new media.

Potential topics engaging with new media surveillance might include, but are not limited to, assignments and lessons that address any of the following:

– political economy of social media platforms

– data mining, collection, storage, and the use of this data by a range of actors

– use of social media by law enforcement agencies

– customized/targeted advertising

– tracking software/cookies that monitor consumer behavior/patterns

– critical interrogations of consumer power and new media

– user/student perspectives on data mining and privacy issues

– social classification and discrimination through data mining

– ethics of data mining

– policy and regulation of data mining

Teaching Media Quarterly Submission Guidelines & Review Policy

Teaching Media Quarterly seeks innovative assignments and lessons that can be used to critically engage with “new media and surveillance” in the undergraduate classroom. All submissions must include: 1) a title, 2) an overview and comprehensive rationale (250-500 words), 3) a detailed lesson plan or assignment instructions, 4) teaching materials (handouts, rubrics, discussion prompts, viewing guides, etc.), 5) a full bibliography of readings, links, and/or media examples, and 6) a short biography (100-150).

Please email all submissions in ONE Microsoft Word document to teachingmedia.contact@gmail.

SUBMISSION DEADLINE: October 31, 2013

Submissions will be reviewed by each member of the editorial board. Editors will make acceptance decisions based on their vision for the issue and an assessment of contributions. It is the goal of Teaching Media Quarterly to notify submitters of the editors’ decisions within two weeks of submission receipt.

Teaching Media Quarterly is dedicated to circulating practical and timely approaches to media concepts and topics from a variety of disciplinary and methodological perspectives. Our goal is to promote collaborative exchange of undergraduate teaching resources between media educators at higher education institutions. As we hope for continuing discussions and exchange as well as contributions to Teaching Media Quarterly we encourage you to visit our website athttp://www.teachingmedia.org/