Reviewing Rodarte: Topographies of Collaborative Thinking

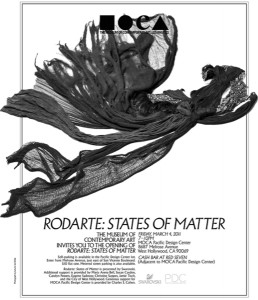

Rodarte. States of Matter. March to May 2011. Installation. Museum of Contemporary Art Pacific Design Center, Los Angeles.

April Durham, 2011

The installation of the work of fashion and costume designers Laura and Kate Mulleavy (Rodarte) at MOCA-Pacific Design Center in West Hollywood represents a departure from the usual displays of fashion seen at fine art institutions in the recent past. Art world curatorial projects with fashion designers have resulted in an often-unsatisfying collision of designer labels within the institutionally separate but perhaps not so different (from the high-end shopping district) space of the museum. For example, the joint project between Marc Jacobs (Louis Vuitton) and Takashi Murakami for MOCA in 2007 resulted in a “product line” of wallpapers, handbags and day-minders that neither reinvented nor really disrupted the LV label, the Murakami oeuvre, or the curatorial habits of the museum. Because States of Matter is conceived as a hypertextual activation of synchronous and divergent narrative maps that link the “clothes,” the relationships among the collaborators, and the space of the museum and the city, this “fashion show” represents a significant reconsideration of the rendezvous between art contexts and fashion designs.

usual displays of fashion seen at fine art institutions in the recent past. Art world curatorial projects with fashion designers have resulted in an often-unsatisfying collision of designer labels within the institutionally separate but perhaps not so different (from the high-end shopping district) space of the museum. For example, the joint project between Marc Jacobs (Louis Vuitton) and Takashi Murakami for MOCA in 2007 resulted in a “product line” of wallpapers, handbags and day-minders that neither reinvented nor really disrupted the LV label, the Murakami oeuvre, or the curatorial habits of the museum. Because States of Matter is conceived as a hypertextual activation of synchronous and divergent narrative maps that link the “clothes,” the relationships among the collaborators, and the space of the museum and the city, this “fashion show” represents a significant reconsideration of the rendezvous between art contexts and fashion designs.

While the fashion blogs reported that the sisters chose selections from the Fall 2008, Spring 2010, and Fall 2010 collection ((See for example: http://laist.com/2011/03/04/rodarte_exhibition_featuring_black.php, http://www.stylelist.com/2011/03/03/rodarte-moca-exhibit/, http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster/2011/01/jeffrey-deitch-bringing-fashion-house-rodarte-to-moca-pacific-design-center.html, or http://www.mediabistro.com/unbeige/las-moca-readies-rodarte-exhibition-an-out-of-body-experience_b11380)), the installation exceeds the representation of hip fashion design. States of Matter is not merely about the interesting costumes from Black Swan (2010) and not at all about offering a consumer product for sale in the museum shop or the Melrose boutique; instead it reflects the conversational narrative of a multi-actor site specific creative practice, which has developed out of the exchange between the designer-sisters and their other collaborators in relationship to the institutional context in which the presentation occurs. This engagement presents the fashion/art dialog as a hyperlinked narrative topography involving the history of art, cinematic and literary narrative, and a gestural memory of the bodies that might occupy the space/time accounts being rendered. Further, it navigates the history of the museum as a colonizing institution for culture ((See for example, “Census, Map, Museum” in Anderson 1991.)) in relation to the geography of Los Angeles as a haunted series of nodes in a larger complex of fashion spaces, by rendering a web of connections that critically engages networks linked to consumption and subjectivity relative to these spaces and institutions. While not a literal “electronic” hypertext as this installation exists in the “physical” world of dresses and lights and workshops and museums and not in the “cyber-world” of the computer, the piece nevertheless expresses a generative reconfiguration of narrative and art-making that traverses the “tactile” and the “coded” in a way that is very similar to what we experience when navigating a site on the internet. So while materially different from an electronic text, States of Matter shares an experiential, gestural, and narratological structure with texts that are more traditionally considered “hypertexts.”

In Hypertext 2.0 from 1997, George Landow offers a detailed discussion of hypertext as a body of “linked texts that have no primary axis of organization” (36). Contextualizing this within Derridian notions of [de]centered language and Deleuzo-Guattarian concepts of relational rhizomes with “their thickenings and shifting connections …[of] network-like structure” (40), Landow describes much of what now comprises a broad experience of the textuality of everyday life. Concerned mainly, in late 90s literary discourse, with legitimizing and enlivening the field of criticism around electronic texts like Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch and Patchwork Girl by Shirley Jackson or web-organized research projects, Landow nevertheless describes a kind of intertextual referentiality that certainly extends to alter-electronic ((I would like to be clear that I do not really find anything to be “non”-electronic as we certainly know that data is conducted along electronic circuits in biological as well as mechanical and digital. Differentiating these types of delivery systems in a polemical manner is not an accurate or particularly interesting consideration. In fact, as the systems achieve similar results, the methods and structures are different only in terms of style.)) “texts” as well.

Landow desires, in a way that also seems historically situated in the late 90s, to distinguish electronic texts containing explicit links to various data packets held within the text from printed codices whose hypertextual references can only ever be implied by the hinted relationships either contained some other place in the book or found generally in the canon of printed literatures and collective cultural memory. While this is an appropriate differentiation, and it would be bizarre to insist that the hypertext implied by Joyce’s footnotes in Ulysses or Derrida’s specters in his visitation on Marx, are the same as those of a webpage or a Storyspace novel, the fourteen odd years since the publication of Landow’s book have resulted in a widespread, almost naturalized, integration of hyperlinking as a way of thinking, a cognition model appropriate to a post-industrial, late Capitalist, intensely fragmented narrative topography of life. The most banal example of this is played out in “social” networking websites where navigating the neighborhood of historical memory, significant event, and everyday life is a constant movement among webs of various acquaintances and institutions representing and expressing tiny packets of experience in a linked and polycentric set of connections.

Considering States of Matter, in hypertextual terms requires a close look at the material work and the experience of viewing it. The installation was presented from March to May 2011 on two floors in the little tower that is MOCA’s space at the Pacific Design Center. Moving from the diffuse but Spring-bright Los Angeles sunshine into the velvety blackness of the first floor exhibition space places visibility, normally an imperative for optimal art-object gazing, into jeopardy. With the pause needed to acquire visual bearings, there comes a moment of precarity in which the floating dresses, the pool of black on the floor which frames them, and the awkwardly exposed clutch of lights in the middle present a menacing mise-en-scene: uncertainty is the violent affect and fight or flight the reaction. There is a sense of stepping onto Mr. Toad’s ride without having known you were doing so. Abruptly this little museum trip has become an encounter with a dark narrative, one in which the logics governing vision, form, and time are cracked and scary in their very subtlety; continuing into the space means navigating the “sense” of the illogical. You adjust yourself quickly so your friends don’t notice that you were frightened and begin to more coolly examine the forms, careful to stay behind the white lines delimiting the safe space.

The subtle, pseudo-horror/fairytale frame is the first clue that what is here is not simply trendy fashion for film and magazine, the rave of all the ready-to-wear blogs. Rather, there is a sense that a bent and backwards story, drawing on a long personal and cultural history of design and relationship, of bedtime stories and conceptual analysis, is being unfurled, for the readers of these objects and for the institutional environment. We know that Rodarte comprises a team of sister-designers who appear, from the videos of their runways shows, very private and a bit shy, and that further, they work closely with other artists on the non-clothing elements of this show. So the situation where a multi-actor, site-specific working group engages in a creative practice that also challenges the institutional contexts in which they are involved becomes foremost to considering the multi-nodal diagram of narrative unfolding in this work. Further, the dialog has a strange logic governing it, one that is based on faulty memory, erroneous maps, and cracks in the looking-glass that shift what is visible from self-contained wholes to tenuous, layered, and non-linear topographies of narrative: what can b e known disrupts what is expected.

e known disrupts what is expected.

There is a dense recent history of artists working “collaboratively,” either toward expanding individual practices as with Claes Oldenberg and Coosje von Bruggen or toward creating environments where individual contributions could be combined into a cohesive whole and thereby manifest a non-heirarchical subjectivity as in the Womanhouse project organized at CalArts by Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro in the 1970s. While these working processes have provided interesting interruptions in the normative idea of a singular, sublime, creative genius, they have mainly been subsumed by the institutional practices they were disrupting. Coosje is always listed second to Claes (as wife and supporter of the real artist perhaps) and the Dinner Party project, which involved 400-plus participants to create, is always attributed to Judy Chicago as an individual artist. Alternatively, the multi-actor site-specific working group I am describing, mobile and transitory in its materiality, shifts a notion of collaborative participation away from the “mass” and toward a relational exchange among actors in a network of sitting, doing, making, telling, presenting, and changing. States of Matter, especially as it is not claimed institutionally as a “collaborative art work,” has the participatory structure involved in film making or event production but allows for the maintenance of individual identities, however precarious, within the context of its moment of engagement.

Curiously the virtuality of the dim and disorienting space of the installation collides gently but powerfully with the actual physicality of the space. There is a subtle movement around and among the notions of visibility, presentation, narrative, and fashionable bodies that does not create a new spectacle, fashion-show-cum-art-object, but invents a resonant diastolic/systolic exchange between the actual space the body of the viewer is occupying and the virtual space of what the objects, the room, and visuality are becoming. This engages in an unexpected way with Jacques Rancière’s notion of the aesthetic-politic wh ere a “community” of the ignored becomes a subject for consideration. This is not a community of self-actualized subjects but a collection of entropic waste elements that gather for the moment, are always precarious, and which ruptures the sensible. This rupture is, for Rancière, the aesthetic action of politics and the politic description of aesthetics. While ultimately his position of aesthetics and politics leaves something profoundly unconsidered, the formulation of exchange between a perceived whole (the self-identified subject) and the monstrous garbage left off by the energy it takes to constitute that subject possesses a virtual energy of its own. Merely by existing, moving through spacetime in a kind of disregarded thermodynamic process, this entropic offal pushes hegemonic systems of vision and visibility, wealth and power, labor and production into a state of becoming that eludes, however momentarily, containment by the established and normative institutions.

ere a “community” of the ignored becomes a subject for consideration. This is not a community of self-actualized subjects but a collection of entropic waste elements that gather for the moment, are always precarious, and which ruptures the sensible. This rupture is, for Rancière, the aesthetic action of politics and the politic description of aesthetics. While ultimately his position of aesthetics and politics leaves something profoundly unconsidered, the formulation of exchange between a perceived whole (the self-identified subject) and the monstrous garbage left off by the energy it takes to constitute that subject possesses a virtual energy of its own. Merely by existing, moving through spacetime in a kind of disregarded thermodynamic process, this entropic offal pushes hegemonic systems of vision and visibility, wealth and power, labor and production into a state of becoming that eludes, however momentarily, containment by the established and normative institutions.

The narrative elements of the installation expand as the eyes grow accustomed to the darkness and although visibility is constantly foiled, the details further weave a loose, disjointed narrative that matches the construction of the elements. Dresses float above the glossy black pool like webbed remains of something that might have covered a human form but which might also be the shadow of gowns remembered, glimpsed fleetingly in the reflection of a plate-glass window. Little tutus, made famous from their appearance in a popular film, rotate from an apparatus in the ceiling that turns slowly so that the traces of the gestures made by the ballerinas once wearing them (the bad ballerinas as these tutus are black) remain while the dancer is only an ill-conjured memory.

The long, columnar gowns are fabricated from feathers, shreds of cheesecloth and silk, and vinyl that has been irregularly embroidered to look like seared, blackened flesh. Membranes of delicately jeweled lace are overlaid by scraps of interfacing, a textile that is normally used to give fabrics varying degrees of stiffness, but which here has been exposed and pulled apart, torn into what appear as webs abandoned by spiders, long gone after digesting the bodies of their prey. Made only more elegant by the fragile connections of each part, the dresses appear forsaken but not abject, in some ways empowered by the role granted them as imagined armor for pretend encounters at gala events where the war is in the social maneuvers and not in the actual bodily contact. A conversation is revealed, based on the viewer’s willingness to slowly examine the multiple layers comprising the narrative topology, and acts as an echo of dialog that isn’t heard properly and is left resonating only in the places of desire and remembrance, simultaneously past and future. It is a dialog of imagination but also of forgetting, where what was discussed and what was hoped for, all that is implied by grand elegance and graceful gesture, slips reality and ebbs away in the dim frame of the museum gallery-cum-faulty memory bank.

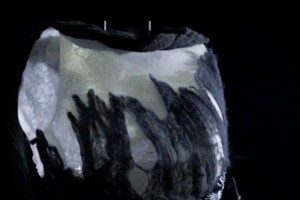

Adding a further strangeness to the shapes the gowns assume here are the forms supporting the clothing; made from thin layers of resin and reflecting an awkward relation to the human form, not idealized feminine mannequin and not runway model or waif-like actress, they seem closer to dehydrated, translucent columns of skin, that while only visible in slivers, support the dresses as a frozen recollection of a body that can merely be conjured as approximation. This shifts the ongoing normative representation in fashion of feminine ideals into the space of 18th century anthropology, where tattooed human skins were preserved for display in French natural history museums. The “body” filling the Rodarte designs are ghosts of forms, decentered from the institutional idea of “body,” barely present and if not exactly ungainly, definitely ill at ease and fragile. Further, they render the dresses more like wisp y pieces of architecture, columns from a Neo-Classical structure visited on a third grade field trip and remembered incorrectly but significantly nonetheless. These hyperlinks establish connections among a dis-functional set of nodes, separated by vast desert voids and refusing to coalesce into coherent and known structures; they evoke instead an emergent space of perplexity or stupefaction, that Avital Ronell calls “[a] corollary to knowing…[where] ignorance has its own story, a story that needs to be told, but one, perhaps, that can spell only ruin” (29).

y pieces of architecture, columns from a Neo-Classical structure visited on a third grade field trip and remembered incorrectly but significantly nonetheless. These hyperlinks establish connections among a dis-functional set of nodes, separated by vast desert voids and refusing to coalesce into coherent and known structures; they evoke instead an emergent space of perplexity or stupefaction, that Avital Ronell calls “[a] corollary to knowing…[where] ignorance has its own story, a story that needs to be told, but one, perhaps, that can spell only ruin” (29).

As with any good story, more pages need to be turned, more links associated, to get a fuller picture of what’s going on, if indeed anything is going on. The narrative presented by the gowns suspended in this abyss, while felt, reveals itself slowly as a multi-cursal path that goes beyond the desire to possess and to see in the deep, velvety darkness. One needs to enter as it were, the other side of the mirror, seeking the continuation of the story upstairs. So one proceeds, directed finally by the closely hovering security guard, to a stairway portal providing a nauseating, flickering, fluorescent glow of purpled white light, illuminating the path to additional components, further data, informing this story.

At the top of the stair another room contains three groups of white costumes: to the left, a set of long dresses; in the center against the back wall two rotating tutus; and on the left two Grecian/1960s style cocktail dresses and a single tutu. For a moment all of the fluorescent tubes flanking the room have illumina ted and the space is saturated with uncomfortable, institutional light of another variety, the kind from high school gymnasiums after the dance or from the hallways of the county hospital at 11:30 on a Saturday night. Then they go out, these lights, leaving not exactly darkness, but with just a few purple tubes flickering, the gloom is palpable and resonates again with some other uncomfortable experience involving an exploded appendix or lost awkward embraces. Throbbing on and again rendering the delicacy of the objects barely visible, the lighting makes you doubt your ability to actually observe the objects, and your desire to gaze without limitation at the deeply fragile and frightening delicacy of the gowns is foiled. There is a disruption not only in expectation but in possibility for viewing, for acquiring, and therefore for containing. Knowing has to be left up to something that is subtler and less reliable than close, detached observation.

ted and the space is saturated with uncomfortable, institutional light of another variety, the kind from high school gymnasiums after the dance or from the hallways of the county hospital at 11:30 on a Saturday night. Then they go out, these lights, leaving not exactly darkness, but with just a few purple tubes flickering, the gloom is palpable and resonates again with some other uncomfortable experience involving an exploded appendix or lost awkward embraces. Throbbing on and again rendering the delicacy of the objects barely visible, the lighting makes you doubt your ability to actually observe the objects, and your desire to gaze without limitation at the deeply fragile and frightening delicacy of the gowns is foiled. There is a disruption not only in expectation but in possibility for viewing, for acquiring, and therefore for containing. Knowing has to be left up to something that is subtler and less reliable than close, detached observation.

Still it is possible to ascertain a group of long white dresses reminiscent of the long black ones on the first level, where sheer white, lace has replaced the translucent black cheesecloth. Curiously, this is not the carefully constructed lace of couture fashion; rather it is the $1.79/yard lace from the Sunday swap meet at the Drive-In in Santa Fe Springs. This is the kind of lace that doesn’t distinguish itself by beautiful arabesques and intense brocaded figurations broken up by delicate webs of silk; rather, it features a small non-descript, stylized rose repeated every 1.5 inches ad infinitum and the poly-blend is wash and wear. The forms are all the more peculiar for this choice when contrasted with the other unusual wooly, velvety fabrics used for the bodices and yokes. Resembling wedding dresses hanging from the rotating rack at the dry cleaners rather than new gowns in a shop window anticipating a romantic future for consumer-brides, these forms shift between fashion and architecture, a past event and a dreamed structure. Further, considering the strange combination of materials presented here, they shimmer metamorphically between something like a uniform, something like armor, something like furniture. They mostly sport wide shoulders lik e those of a 1940s evening gown and the snipped in waist of a Victorian frock coat. One short gown has Alpaca fur epaulets and capped sleeves and another appears to be made from 19th century horsehair upholstery. While ostensibly “wearable” in the end, the materiality of these pieces evokes a notion of the hospitable armchair disrupted by the demands of the structured uniform. There exists a kind of strategic folly in the links among the materials, the forms, and the fashion in this grouping, which generates an uneasy conversational trajectory about relationships, partnerships, and expectations for the future that remain inconclusive and fraught. They are faulty links that defy the site map directing those ever-present data gathering spiders toward organizing the information such that it is navigable and proper.

e those of a 1940s evening gown and the snipped in waist of a Victorian frock coat. One short gown has Alpaca fur epaulets and capped sleeves and another appears to be made from 19th century horsehair upholstery. While ostensibly “wearable” in the end, the materiality of these pieces evokes a notion of the hospitable armchair disrupted by the demands of the structured uniform. There exists a kind of strategic folly in the links among the materials, the forms, and the fashion in this grouping, which generates an uneasy conversational trajectory about relationships, partnerships, and expectations for the future that remain inconclusive and fraught. They are faulty links that defy the site map directing those ever-present data gathering spiders toward organizing the information such that it is navigable and proper.

Adding further tension is the pair of Grecian-style cocktail gowns, of the bosom-hugging style that looked so good on the luscious 1960s Elizabeth Taylor of BUtterfield 8. Suspended over a pile of tumbled light ballasts fitted with red and white fluorescent tubes, these party dresses are randomly striped with what appears to be blood, dumped Carrie-style from the ceiling, but mopped up fastidiously before the party started. Further, the little tutu rotating in this composition has a blossom of blood at the navel in something that definitely is not a flower, but seems to be coming from a stab wound. Opposed to the ersatz wedding gowns in the space, they form a kind of shrill but beautiful argument, a narrative trajectory that, again, Liz might have followed Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolfe, profoundly articulate but completely incomprehensible. Then you remember an image of the sister-designers posed beside the ostensibly blood-soaked frocks and wonder if their take on expectations for femininity is as gothic and problematic as the image implies.

The sweetly white tutus twisting center room in front of their ladder of shivering light fixtures take on a new relationship to the grace of the ballerina and the desire of little girls pirouetting together in their bedrooms or grown sisters discussing deconstruction and post-structural narratology over the cutting table in their Pasadena studio. The groupings upstairs seem a broken-mirror inversion of the black, frightening elegance on the first floor. The two levels begin to resonate one with the other and a weird narration of tentatively remembered conversations, songs sung into hairbrushes, and longing for something that resembles your mother’s dreams starts to pulsate through the space. You look askance at your friends and wonder if they also feel the floor opening up. Then the lights flash again, and your eyes twitch and you remember the other actor in this network, Alexandre de Betak, a set designer who has worked with Rodarte on their runway shows.

and a weird narration of tentatively remembered conversations, songs sung into hairbrushes, and longing for something that resembles your mother’s dreams starts to pulsate through the space. You look askance at your friends and wonder if they also feel the floor opening up. Then the lights flash again, and your eyes twitch and you remember the other actor in this network, Alexandre de Betak, a set designer who has worked with Rodarte on their runway shows.

At first, the fluorescent tubes, seen in the context of MOCA, reference the 1960s minimalist sculptures of Dan Flavin. But the lights in States of Matter cycle uneasily, evoking instability rather than the sublime transcendence of modernism. They break from the institutional reference and link more directly to an engagement with their own recent history in the presentation of fashion, and in that they extend the narratives mapped by the work in this exhibition. In fact, they seem to reference more the malfunctioning lights in the cheap shops on South Fig in Highland Park than any real art historical objects. The disturbing color choices (bright white and mauvey-purple) flicker and flash in an irregular rhythm that is difficult to watch. Part techno club set, part low rent shop window, they irritate the viewing experience, further making visibility a problem, foiling the possibility for clear, sustained gazing, for direct encounter between body and objects, for observing quickly and dismissing or consuming. The problem of vision does connect, via layered, multiple, and fragmented links, to more recent concerns with perception, cognition, and epistemology through the forced connections to fashion presentation.

For Rodarte’s Spring 2011 collection runway show, de Betak organized an unconventional presentation with some of the same materials used in the States of Matter installation. The room was emptied of runway or even chairs and instead wooden pallets were stacked on the floor and leaned against the walls between which were placed fluorescent ballasts with white and yellow tubes (link to YouTube video of show). The minimal environment nods to 1960s sculptures from which it might take its inspiration, but the narrative relationship of the space to the architectural clothing designs from this season’s line has more to do with what architect and urban planner, Ignacio de Sola-Morales, calls the terrain vague. This is the no-man’s land of urban and suburban abandoned public spaces: closed strip malls, weed choked vacant lots, and industrial complexes that have been forsaken mid-construct such that foundations and partial walls provide perfect pallets for illegal artistry and drug overdoses. Sola-Morales discusses this space as one of pure potentiality: emptied of the perhaps oppressive force of normative productivity, these derelict spaces offer a chance for a creativity that comes from the margins, one  that could be liberating but which is also dangerous and frightening. Linking to a dead zone like this is further opening a connection to the illogic of the backside of the looking-glass, a place of pure potential because the contained knowledge of rationalism is made monstrous such that it needs to generate something different. This difference, however, becomes part of a larger network of knowing, doing, and being, an affective complex of shifting, pulsing movement that animates narrativity in subject/object relations in a continual and precarious movement that is both destructive and constructive at once.

that could be liberating but which is also dangerous and frightening. Linking to a dead zone like this is further opening a connection to the illogic of the backside of the looking-glass, a place of pure potential because the contained knowledge of rationalism is made monstrous such that it needs to generate something different. This difference, however, becomes part of a larger network of knowing, doing, and being, an affective complex of shifting, pulsing movement that animates narrativity in subject/object relations in a continual and precarious movement that is both destructive and constructive at once.

The lights in the States of Matter installation engage with the fractured memory of the gowns and the institutional memory of the museum/museum-goer in a way that joins a paradigm of creative desire, moving in a space not logical to normative productivity: it is a desiring mode that knows only the force of its own creativity. The exhibition does not inhabit an entirely known space, but rather diagrams multiple layers of topographical narration, linking stories that move in disjointed patterns, and which only make sense when the irritation and fear they evoke fail to be “righted” toward a comforting and rational containment. The quivering lights, the levitating gowns, the skin-like crusts that serve as human forms all combine in a linked dialog with the actors in the network, figuring a graceless dance that is the very nature of engaging with dreams, desires, networks, labor, heartache, failure, uncertainty, and fear inherent in creative practice, but also in the very stuff of living.

Works Cited

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London and New York: Verso, 1991. Print.

Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx: the State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International. New York: Routledge, 1994. Print.

Landow, George. Hypertext 2.0: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. Print.

Rancière, Jacques. Dissensus: on Politics and Aesthetics. London and New York: Continuum, 2010. Print.

Mulleavy, Laura, Kate Mulleavy, and Alexandre De Betak. States of Matter. 2011. Mixed media installation. MOCA-Pacific Design Center, West Hollywood, California.

“Rodarte Spring Summer 2011.” Youtube. 15 Sept. 2011. Web. 5 May 2011. <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GzvbSGCur1E>.

Ronell, Avital. Stupidity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002. Print.

Solà-Morales, Ignacio. “Terrain Vague.” Anyplace. Ed. Cynthia C. Davidson. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1995. 118-123. Print.